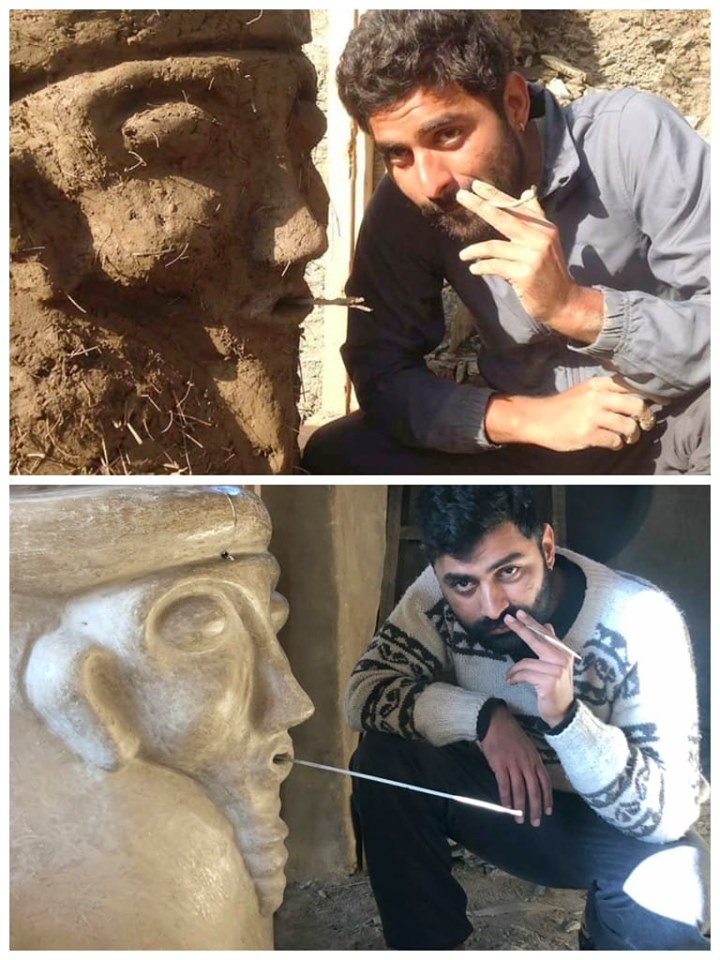

Join my One-off Clay plaster workshop

|

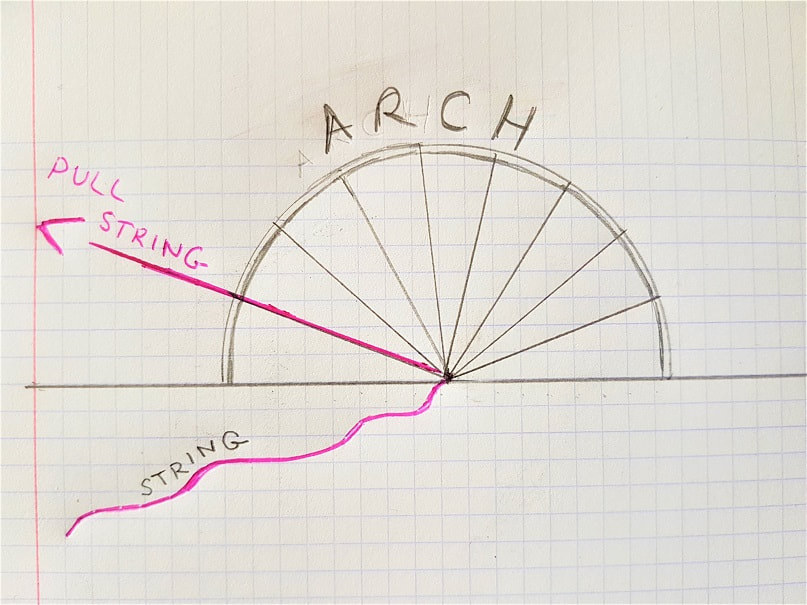

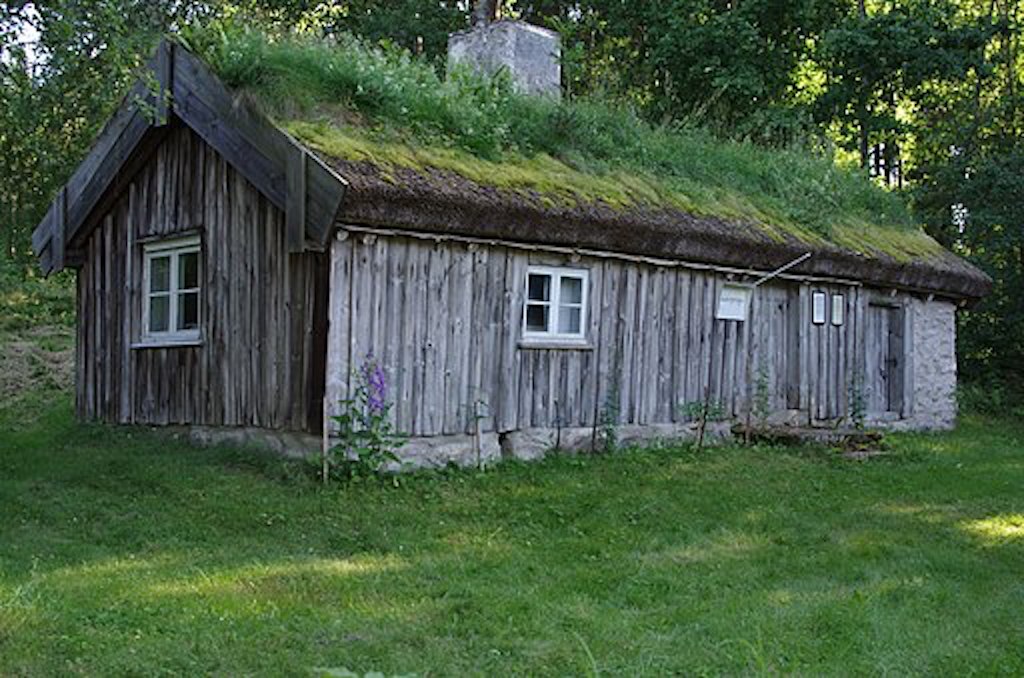

When you learn how to create gorgeous clay plasters from the earth around you, you begin an amazing journey into natural building. Join me in Romania this summer to learn this life-changing art.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed