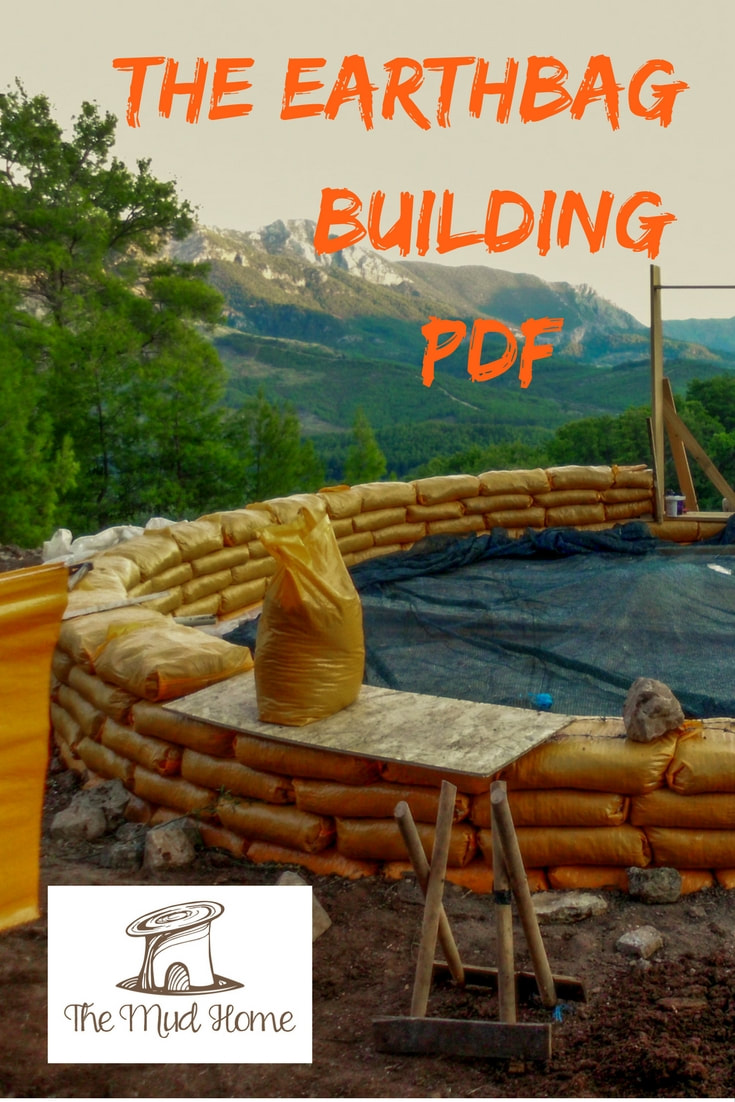

An Earthbag House in 7 Days? |

|

| 7daysmaster.pdf | |

| File Size: | 6024 kb |

| File Type: | |

Chapter One - A Preposterous Proposal

Feryal and Baykal Feryal and Baykal

So I left Mud Mountain one day, and fell into an earthbag workshop the next. Just like that. One day I was in my mud home, the next I was camping in a field, the dirt foundations of a roundhouse leering at me. And as usual I was nursing the hunch that I didn’t know what I was doing.

I’d been worrying about this workshop for months. Far more than I was worrying about moving off my land, or selling my house. Because attempting to build a house in seven days during an earthbag workshop is of course ridiculous. “Baykal, I really don’t know if we can do this, you know.” I held the tip of a green hose and measured the circle of the roundhouse-to-be. We had just breached the month of September, but the sun didn’t seem to have caught on. It was a sky borne iron branding the top of my head. Baykal pushed the brim of his straw hat up. “Ah come on Kerry, iss twelve people. We gonna do it. I got back up. No worries maan.” He patted my shoulder. Back up. Those famous last words. I bit my lip and completed the circle. Baykal smiled peacefully, as is his way. I’ve known Baykal and Feryal (the hosts of the workshop) for 15 years now. That’s a long time. That’s the only reason I agreed to such a preposterous project. I trust them both. They make things happen. But a 5 metre diameter round house (that ended up being 5.5 by the time we laid the bags) with a bathroom added? From foundations to roof? With a team of people who had never built before? Even for a maverick like me it looked fairly undoable. And there was so much that could go wrong. What if it rained? What if the windows buckled again? Would the participants be up to the task? “What if they just run off to the beach and never come back?” Asked one friend. Yes...what if? So two weeks later, by the time the first earthbaggers began filtering in, with their tents and their camping mats and their absurdly incongruous dietary requirements, my nails had been bitten so far back, even the dirt couldn’t skulk under them. And it was hot. Far hotter than I had predicted. Too hot for September. I huddled on Feryal and Baykal’s terrace with the first three arrivals, squeezing myself into a rectangle of shade. “I saw a youtube on building an earthbag earthship underground. Do you know how to do that?” Taylan sat sucking a cigarette around the breakfast table. Every now and again he’d remove it to gulp from a plastic bottle swirling with Cola and Nescafe. Taylan worked for a bank. God knows which one. But whichever it was, they obviously didn’t give him enough to do, because he’d devoured every video on earthbag building Youtube had ever published. I allowed the question to scud breezily over my head, because A: I’m more of an ‘Erm...let’s see if this’ll work,’ kind of builder,’ and B: I had but the haziest of ideas how to make an underground earthship. I pushed some bread in Taylan’s direction. “No no no...No carbs for me. No way. Just protein and fat,” he said smearing an egg with butter. He was tall, and I could tell from the way he sat, he’d spent far too long in an office. “Our intestines weren’t made for grains. They give you cancer,” he grinned broadly exhaling a dark miasma of smoke. “I’m not sure I agree with that.” Emma, my vegan yogi friend tucked into her chia muesli. “I’m going to have an issue with the smoking too, aren’t I?” She said, her British accent leaping out at me in familiarity. I nodded. A lot of smoking goes on in Turkey. It’s par for the course. “Try this Emma. It will change your world.” Taylan handed her his caffeine adulteration and grinned. It slurped ominously in the bottle. Emma shuddered slightly. She was elegant and slim. I wondered briefly if she’d know what to do with a spade. It was then a third voice piped up from the other end of the table. Followed by a muscular arm stretching toward the cheese. “Hey, can I have some of that muesli? I’m going to need some different kinds of energy for this. I’m going to need a lot of energy. A lot of food.” Domi was from Hungary. And no I didn’t make that up. He stood and stretched. He didn’t look like he’d been sitting too long in an office. He looked like he’d just hiked down from Matterhorn. I must admit, that first morning before the course began, every aversion I harbour of working with people was awakened; the aggravation of pulling a team of conflicting personalities together, the precarious juggling of individual needs. The sheer eccentricity of us all. We were like random pieces of a jigsaw puzzle made of razor blades. I inhaled slowly and exhaled slowly. Many times. The day opened and closed like a camera lens. The sun marked its movement in fiery steps. Despite the sun cream and the hats, I could see Domi, Emma and Taylan reddening before my eyes. It was hot. Far too hot for building. By evening most of the group had assembled. Tents popped up all over the garden. By chance or design each was a different colour creating a rainbow hobbit’s-ville of canvas. Just three participants were missing; one young woman was coming the next day. But we were still expecting two Turkish guys from a seaside town up the road. I sat on the house terrace with Feryal. We waited. It grew colder. The stars plucked at the darkness forming irregular patterns, their angles sharp and brisk. We waited longer.

It was 11 pm when Baykal’s car pulled up to the house. The headlights flicked off, and I blinked as my retinas readjusted to the pitch. Doors creaked open, and two men staggered out. I noticed they were carrying disconcertingly small rucksacks. “We have a problem,” Baykal threw his keys onto the table and grinned at me. They forgot their tent.” The men giggled sheepishly. “And their sleeping bags.” “No no we found one. Someone gave us one!” said the taller of the two men. This was Kemal. He was foreboding in height and expression. He lumbered up the terrace steps slowly. Bear-like. And flopped onto the hammock tied between the terrace supports. Collapsing on my cushion, I guffawed. Well, what else could I do? *** All too soon it was morning. The sky was a cool metal alloy. 11 glove-clad earthbaggers gathered in the foundation brandishing picks and spades. To me, used as I am to a maximum team size of four, it looked like a mud army. The dark mountain of Kemal shuffled about sniffing. His smaller friend blinked and yawned beside him. The pair had slept on the balcony and were now both sleep-deprived and cold. “Right, we need to clear the foundation so that it’s a proper trench. The rocks come on the inside of the circle, the dirt on the outside. We’ll use it in the bags.” Eleven pairs of eyes scrutinised me. Each person would clear about a metre or so of foundation. This was the moment of truth. Would they be able to dig? I looked up to see Emma, spade over shoulder. Taylan, who was still smoking, leaned on a pick. Domi was limbering up. And then it happened.

Mud magic. I don’t know what it is about building mud homes, but it does something to people. Something odd. Something beautiful. As soon as human hands touch the earth, miracles are unleashed. The dirt circle casts its spell. Within minutes people shifted into teams. Of their own accord. Some dislodged rocks and hard earth with the picks, some pulled the rocks from the ring and others shovelled the dirt out. The foundations became a circle of colourful movement. I could see Domi’s muscles flexing in the dirt. Taylan turned, a whirlwind of energy and motivation. He ran around the circle sweating, smoking and making everyone laugh in equal measure. “Eh, look at ‘er. Like an American soldier,” said my camera man. He was filming Emma, who clearly had held a spade before, because she was shovelling that dirt like a pro. She would shovel like that for days, striding over the earth in her Doc Martins, auburn hair pulled back. She was indefatigable. The foundation was cleared in an hour that morning. And it was filled with rocks and rubble by mid-afternoon. I marvelled as I beheld this miscellaneous team of mud Gods and Goddesses. 5 men, 5 women, 5 international, 5 from Turkey, all finding their place. Their skills. Their strengths and their weaknesses. By day’s end I began to see, each idiosyncrasy was a blessing, not a curse. Each individual was so valuable. I needed the muscle and the laughter, the precision and the vision, the sensitive and the tough, the emotional support, the spiritual connection, the DJ, the stamina. I even needed those damn Youtube videos. To anyone hoping to build out there, this is the key: Each team member is a dirt angel in disguise. And each has come for a reason. Mark my words, at some point in the build, no matter how unlikely it may seem, you will need each and every one. If you think you only can use a bunch of power houses, you are way off the mark. So far off the mark your walls are going to topple. Probably because you have no one to check if they’re straight. Your team will die of hunger. Or there’ll be no humour. No beauty. For magic, you need the alchemy of it all. We had that alchemy. From day one. And it created an energy of will and manifestation that far surpassed the feasible. “It won’t work.” Taylan sat on a cushion inhaling yet more from his bottle of brown horror. It was mid-afternoon and the group was assembled for a theory session on the terrace. “We can’t finish the house in a week.”

Murmurs rippled through the team. Everyone was squatting on cushions supping drinks and fanning themselves. “Are you telling me it’s impossible?” I looked him in the eye raising a defiant eyebrow. “Yes. It’s impossible. I mean, look at it logically Atulya. We have no experience. We just filled in the foundation.” He was shaking his head, brow furrowed. It was that very moment I realised how much I need a rational sceptic. I love them. They are to me what liquid hydrogen is to a rocket engine. Feeling the power of the challenge surging into my upper body, I grinned at Taylan. I’d liked him since the moment he’d called to book for the course and told me he was going to make an earthbag animal shelter. Despite his strange paleo-caffeine diet and his lung-obliterating smoking habit, he was golden hearted and truly invested in the project. “Ah nothing is impossible. So we’ll see, my friend. We’ll see.” I chortled, knowing from the depths of my soul that anything could happen. Anything. Because this was mud. And magic was afoot. The first day closed with 10 earthbaggers slurping and stomping in a huge pit of earth plaster. We were preparing a batch a week ahead, so it could percolate. There was mud everywhere. In feet. In hair. All over faces. Taylan, cigarette firmly glued between his lips, chortled heartily as he opened the spigot to spray water into the mud pit. Emma helped me bolster the sides of the tarp with big rocks. It was one happy, dirty mess. As darkness pushed us off the land, I noted happily that we were on schedule. The foundations and plaster were complete. The stem wall was Tuesday’s job, after which we would push on up on the earthbag wall. I dared believe it. Was it possible? A house in seven days? But just as a shoot of hope began to flourish, something happened. As usual. It hovered over the seedling of optimism like a large, ill-placed foot. “Kerry, we may be have a problem.” Baykal loitered next to me, one eye on the mud party, the other on his phone. He pushed the square of tech under my nose. It glowed in the fading light. “Oh no,” I murmured, grabbing the phone and staring at it closer. The weather app showed a storm on the horizon followed by two days of rain. And the storm was arriving tomorrow. We had 10 people in tents – including myself – only two of which were waterproof. “It can’t be. It’s so hot!” I blurted. “Ah may be it doesn’t come. May be the app is wrong. Sometimes it’s raining. Sometimes nothing. No worries man. May be no rain.” Baykal and I looked at each other and then giggled. It was the laughter of the desperate. Because if it rained we were foiled. And we had absolutely no control over it. *** Of course Tuesday arrived. And so did the storm. And the rain. Tents were washed out. Some blew away. Not to mention the water being cut off. But that is next week’s story. Part Two - The Unravelling

|

A big thank you to all those supporting this site on Patreon.other books by

|

No alcohol is allowed during the workshop, though you may have a civilised glass of wine with your evening meal.

This was the wording in the workshop advert, and I think it was pretty clear. Earthbag is an extreme sport and the last thing I needed was drunkards entangling themselves in the barbed wire or tripping off the earthbag walls. Besides, I wanted to attract serious and dedicated earthbaggers, didn’t I?

Yees.

The frayed ends of day one had been knotted neatly together. We had left the site for dinner in the valley. The night sky slid through the mesh of the pine forests like warm carob molasses. Sweet. Sticky. Though we, after a day of trench digging, were stickier. After dinner, I trotted about the guest house garden, gathering my flock. It was time to drive everyone back to the site to sleep. We had an early start.

So imagine my surprise, as I picked my way through the plexus of orange trees, on finding a scrum of earthbaggers roistering about a bottle-littered table. They were knocking back beer with a vigour and volume one usually associates with Friday night on any given high street in the UK.

Folding my arms, I surveyed the jeering, japing group searching for an instigator. My gaze fell upon a long-haired, bearded chap with a grin.

Gautam from Mumbai.

Any ordinary day, one would never believe that Gautam could be the catalyst for such mischief. He and his partner Kim had flown in from India and were commonly agreed to be the sweetest couple in the history of earthbagging romance. Further more, neither of them had slept for days.

“Oh it was terrible. I really didn’t think we would be able to make it. There were floods and storms everywhere in Mumbai.” Gautam had scooped heaps of air up into his arms on arrival day to illustrate a storm hitting an airport. He sported two dark ellipses around his eyes issue from jet lag and fatigue.

“Yes, it was very frightening,” Kim shuddered. She was pretty and petite. “But don’t worry we’ve come here to work. We will work very hard,” she said and wiggled her head earnestly.

They had indeed worked hard. If a spade needed fetching, Gautam ran for it. If a rock needed moving, Kim slid her work gloves on and moved it. Certainly Gautam and Kim were the epitome of politeness and helpfulness.

“So lovely,” I had said to Feryal.

“Yeah they’re really cute,” she had replied.

Thus, as I approached the wooden table that evening, I blinked and then gulped and then held my breath. Finally I readied myself for sternness. Gautam was rocking on his seat tittering cheekily, “Ooh just one more little drink, one more, then we will come, we promise.” He raised his glass (was that Raki? Oh Lord!) and giggled like a naughty school boy. My heart sank. My stomach sank. Everything sank.

“We’re starting at 7 am, remember? Drink up! I’m leaving in five minutes.” I hovered over the group hoping my presence would sober them up.

“Noo problem Atulya, we can go wiv Baykaaaaal. I already assed him.” To my dismay I saw Taylan, barely upright, clutching the table. He turned two pickled slits of eyes to face me. The vowels and consonants tripped and fell out of his mouth depositing themselves in a slurring heap between my ears. I sincerely hoped Taylan hadn’t ‘assed’ Baykal and swiftly turned on my heel to check. I spied my friend between the orange branches puffing on a roll up. He grinned at me and saluted.

Rules. Order. Are there any to be found in this world of chaos and mayhem?

The rocky shards of the Olympos gorge glowed. Night was knitting the cosmos into a glittering tapestry. Only it was threadbare. The moon had punched starless holes into the sky leaving the constellations to fall apart. I yawned and rubbed my eyes feeling the weight of being team organiser bearing down upon me. Because inevitably someone has to play Atlas, don't they? How could I pull this inebriated straggle together?

It was then I spied our eleventh earthbagger; a young Turkish woman with boots, backpack and a soupcon of ‘attichude’. This was Canan. To my horror she was also clutching a beer bottle. My earthbag mob had got to her first, while I was elsewhere.

“Canan, we have to get you back so we can put your tent up. It’s late. It’s dark. You might need help.”

Canan squashed herself onto the wooden bench and eyed me coolly. She was a curly haired outdoor Amazon. “I can put my tent up anywhere. I don’t need help. I camp alone all the time,” she shrugged, and tilted the bottle to her lips. The rest of my earthbag rabble cheered.

Ooh badass! I thought. And reached for my car keys.

This was the wording in the workshop advert, and I think it was pretty clear. Earthbag is an extreme sport and the last thing I needed was drunkards entangling themselves in the barbed wire or tripping off the earthbag walls. Besides, I wanted to attract serious and dedicated earthbaggers, didn’t I?

Yees.

The frayed ends of day one had been knotted neatly together. We had left the site for dinner in the valley. The night sky slid through the mesh of the pine forests like warm carob molasses. Sweet. Sticky. Though we, after a day of trench digging, were stickier. After dinner, I trotted about the guest house garden, gathering my flock. It was time to drive everyone back to the site to sleep. We had an early start.

So imagine my surprise, as I picked my way through the plexus of orange trees, on finding a scrum of earthbaggers roistering about a bottle-littered table. They were knocking back beer with a vigour and volume one usually associates with Friday night on any given high street in the UK.

Folding my arms, I surveyed the jeering, japing group searching for an instigator. My gaze fell upon a long-haired, bearded chap with a grin.

Gautam from Mumbai.

Any ordinary day, one would never believe that Gautam could be the catalyst for such mischief. He and his partner Kim had flown in from India and were commonly agreed to be the sweetest couple in the history of earthbagging romance. Further more, neither of them had slept for days.

“Oh it was terrible. I really didn’t think we would be able to make it. There were floods and storms everywhere in Mumbai.” Gautam had scooped heaps of air up into his arms on arrival day to illustrate a storm hitting an airport. He sported two dark ellipses around his eyes issue from jet lag and fatigue.

“Yes, it was very frightening,” Kim shuddered. She was pretty and petite. “But don’t worry we’ve come here to work. We will work very hard,” she said and wiggled her head earnestly.

They had indeed worked hard. If a spade needed fetching, Gautam ran for it. If a rock needed moving, Kim slid her work gloves on and moved it. Certainly Gautam and Kim were the epitome of politeness and helpfulness.

“So lovely,” I had said to Feryal.

“Yeah they’re really cute,” she had replied.

Thus, as I approached the wooden table that evening, I blinked and then gulped and then held my breath. Finally I readied myself for sternness. Gautam was rocking on his seat tittering cheekily, “Ooh just one more little drink, one more, then we will come, we promise.” He raised his glass (was that Raki? Oh Lord!) and giggled like a naughty school boy. My heart sank. My stomach sank. Everything sank.

“We’re starting at 7 am, remember? Drink up! I’m leaving in five minutes.” I hovered over the group hoping my presence would sober them up.

“Noo problem Atulya, we can go wiv Baykaaaaal. I already assed him.” To my dismay I saw Taylan, barely upright, clutching the table. He turned two pickled slits of eyes to face me. The vowels and consonants tripped and fell out of his mouth depositing themselves in a slurring heap between my ears. I sincerely hoped Taylan hadn’t ‘assed’ Baykal and swiftly turned on my heel to check. I spied my friend between the orange branches puffing on a roll up. He grinned at me and saluted.

Rules. Order. Are there any to be found in this world of chaos and mayhem?

The rocky shards of the Olympos gorge glowed. Night was knitting the cosmos into a glittering tapestry. Only it was threadbare. The moon had punched starless holes into the sky leaving the constellations to fall apart. I yawned and rubbed my eyes feeling the weight of being team organiser bearing down upon me. Because inevitably someone has to play Atlas, don't they? How could I pull this inebriated straggle together?

It was then I spied our eleventh earthbagger; a young Turkish woman with boots, backpack and a soupcon of ‘attichude’. This was Canan. To my horror she was also clutching a beer bottle. My earthbag mob had got to her first, while I was elsewhere.

“Canan, we have to get you back so we can put your tent up. It’s late. It’s dark. You might need help.”

Canan squashed herself onto the wooden bench and eyed me coolly. She was a curly haired outdoor Amazon. “I can put my tent up anywhere. I don’t need help. I camp alone all the time,” she shrugged, and tilted the bottle to her lips. The rest of my earthbag rabble cheered.

Ooh badass! I thought. And reached for my car keys.

It was two in the morning and I was lying in my tent listening to one, two... no there were three owls calling plaintively in the pine forest surrounding the site. A feisty moon held her ground in the night sky. Under her gaze my canvas resembled the fluorescent blue light of an old British police car. My thoroughly potted earthbaggers had returned at gone midnight, giggling and carousing their ways into their tents. I knew because I had heard them too.

Sleep avoided me. A small hump under my right hip had in the course of the evening mysteriously turned into the K2. It now pushed painfully into my backside. My mind, evil trickster that it is, spied this window of sleepless opportunity. It turned into a mad-thought production line. I was beset by every available concern possible. How can I wake the baggers? They’ll never get up. And I’m responsible. I have to make this house happen. Tomorrow is stem wall day. Gravel-filled bags. But is the weave of the new bags strong enough? Should I add limecrete to stabilise the gravel? We need ash for limecrete. OK I’ll get Baykal to make a fire. Will it rain tomorrow? The app predicted rain. May be it’s wrong. I hope it’s wrong.

It was then I heard a light patter on the tent. The app hadn’t been wrong. Rain was here. And my tent wasn’t waterproof. This was obvious, because it was already dripping ever so slightly to the right of my bed.

***

“So, as is often the case with me, I’ve changed my mind.”

It was 7:30 am. The air was a mushy grey porridge. The advantage of having your group camp on site, is of course there’s nowhere for anyone to run. The team were assembled, albeit staggering and yawning, by our trench. Taylan clung desperately to his Nescafe and cola concoction. Gautam shuffled guiltily into our freshly dug trench, the circles beneath his eyes now veritable bruises. Canan, however, strode up to the site, eyes gleaming, hair flying, looking like Turkey’s answer to Boadicea. And yes, I sighed a little with relief.

“Because these sacks are thinner and the weave looser than the ones I used in my house, I’ve been worrying all night if they’re sturdy enough to hold the gravel. Sooo we’re going to mix it with limecrete. Baykal, can you light a fire and make some ash?”

Many assume it must be a dream to be the host of an earthbag building workshop. You learn how to earthbag and get a house for free, right? Let it be known, the hosting of a workshop is demanding. You have to organise the materials, prepare the site, keep the guests happy, not to mention 11 strangers defecating in your toilet. And then there are the spontaneous plan changes of the batty workshop leader. Baykal stood unmoving, a pillar of calm in a lawless world. “It’s just rained. There’s no dry wood,” he said.

I sighed. The ash in limecrete is crucial. It provokes a chemical reaction that hardens the crete. 11 earthbaggers trained their eyes on me waiting for my verdict.

Baykal scratched his head. “Give me an hour,” he mumbled suddenly. Pulling his mobile out of his leather belt, he began dialing numbers. He walked away from the circle and crooked his head toward the phone.

If I’ve one image of Baykal during that workshop, it’s of him muttering into a phone and making impossible things happen. The phone is Baykal’s magic wand. Numbers are tapped. Words are uttered. And whatever you want mysteriously arrives.

An hour later a VW camper van rolled down the slope and onto the site. Four large bins of ash were hauled out. Lord knows where Baykal found four bins of ash at 8 o’clock on a Tuesday morning. But he did. We were back in business. Limecrete business.

And this in all truth is when things really began to snag and tatter. Perhaps it was because rather than earth, we were working with gravel and lime. You see, it’s the mud that holds the magic. It’s Gaia’s dirt that bonds and empowers. Isn't it?

A brave sun gilded the clouds for a while. I watched Kim shoveling with a spade that was longer than she was tall. Canan, an all-rounder, stirred the 'crete and laid the bags. Despite the previous night’s alcohol binge, the team lacked nothing in dedication. The circle was a gladiator’s arena of frenzy. Wheelbarrows full of limecrete and gravel rumbled over the ground like chariots. Polypropylene bags flew like flags. Everyone was striving for the roof. But by afternoon we were still wrestling with the first layer of the stem wall.

“We’re behind schedule,” I said to Baykal, the incumbency steadily crushing me.

He scratched his chin. “No problem. You just tell me when you need back up,” he grinned.

That night no one drank. They were too tired. Besides it was raining. Hard.

Sleep avoided me. A small hump under my right hip had in the course of the evening mysteriously turned into the K2. It now pushed painfully into my backside. My mind, evil trickster that it is, spied this window of sleepless opportunity. It turned into a mad-thought production line. I was beset by every available concern possible. How can I wake the baggers? They’ll never get up. And I’m responsible. I have to make this house happen. Tomorrow is stem wall day. Gravel-filled bags. But is the weave of the new bags strong enough? Should I add limecrete to stabilise the gravel? We need ash for limecrete. OK I’ll get Baykal to make a fire. Will it rain tomorrow? The app predicted rain. May be it’s wrong. I hope it’s wrong.

It was then I heard a light patter on the tent. The app hadn’t been wrong. Rain was here. And my tent wasn’t waterproof. This was obvious, because it was already dripping ever so slightly to the right of my bed.

***

“So, as is often the case with me, I’ve changed my mind.”

It was 7:30 am. The air was a mushy grey porridge. The advantage of having your group camp on site, is of course there’s nowhere for anyone to run. The team were assembled, albeit staggering and yawning, by our trench. Taylan clung desperately to his Nescafe and cola concoction. Gautam shuffled guiltily into our freshly dug trench, the circles beneath his eyes now veritable bruises. Canan, however, strode up to the site, eyes gleaming, hair flying, looking like Turkey’s answer to Boadicea. And yes, I sighed a little with relief.

“Because these sacks are thinner and the weave looser than the ones I used in my house, I’ve been worrying all night if they’re sturdy enough to hold the gravel. Sooo we’re going to mix it with limecrete. Baykal, can you light a fire and make some ash?”

Many assume it must be a dream to be the host of an earthbag building workshop. You learn how to earthbag and get a house for free, right? Let it be known, the hosting of a workshop is demanding. You have to organise the materials, prepare the site, keep the guests happy, not to mention 11 strangers defecating in your toilet. And then there are the spontaneous plan changes of the batty workshop leader. Baykal stood unmoving, a pillar of calm in a lawless world. “It’s just rained. There’s no dry wood,” he said.

I sighed. The ash in limecrete is crucial. It provokes a chemical reaction that hardens the crete. 11 earthbaggers trained their eyes on me waiting for my verdict.

Baykal scratched his head. “Give me an hour,” he mumbled suddenly. Pulling his mobile out of his leather belt, he began dialing numbers. He walked away from the circle and crooked his head toward the phone.

If I’ve one image of Baykal during that workshop, it’s of him muttering into a phone and making impossible things happen. The phone is Baykal’s magic wand. Numbers are tapped. Words are uttered. And whatever you want mysteriously arrives.

An hour later a VW camper van rolled down the slope and onto the site. Four large bins of ash were hauled out. Lord knows where Baykal found four bins of ash at 8 o’clock on a Tuesday morning. But he did. We were back in business. Limecrete business.

And this in all truth is when things really began to snag and tatter. Perhaps it was because rather than earth, we were working with gravel and lime. You see, it’s the mud that holds the magic. It’s Gaia’s dirt that bonds and empowers. Isn't it?

A brave sun gilded the clouds for a while. I watched Kim shoveling with a spade that was longer than she was tall. Canan, an all-rounder, stirred the 'crete and laid the bags. Despite the previous night’s alcohol binge, the team lacked nothing in dedication. The circle was a gladiator’s arena of frenzy. Wheelbarrows full of limecrete and gravel rumbled over the ground like chariots. Polypropylene bags flew like flags. Everyone was striving for the roof. But by afternoon we were still wrestling with the first layer of the stem wall.

“We’re behind schedule,” I said to Baykal, the incumbency steadily crushing me.

He scratched his chin. “No problem. You just tell me when you need back up,” he grinned.

That night no one drank. They were too tired. Besides it was raining. Hard.

Ah, we humans are like spools of thread. Some wool, some silk, some polyester. Yet until we unravel, the real us is never seen. Our truth is there, always there, twisting and turning within. It is coiled up. Hidden. Often even from ourselves. This is a tragedy. Because our essence is perfect. It is exactly what is needed at any given time. It is the part of us that is miraculous.

It was on day three we all unraveled. One by one.

I pulled back my tent flap on the morning of the third day to an unpredictable sky. One minute it was a morbid grey shroud, the next a cobalt, sun-emblazoned sheet. The wind whipped the tents. They were canvas contortionists bowing and buckling with each gust. I couldn’t decide if it was a dance or a battle they were engaged in.

The night hadn’t been kind. A brisk deluge at 10 pm had flooded one tent. Its occupant had taken over Kemal’s hammock on the balcony, she was now huddled there hat pulled over her hair, blanket up to her chin. Kemal and Gürkan, the two tent-forgetting late comers from day one, had thankfully possessed the foresight sleep at the guest house.

As I moved toward the house balcony for a coffee, I surveyed the garden. All I could see were skirmishes involving pieces of plastic and earthbaggers who were attempting to keep their tents dry.

Finally, the team assembled in front of the house. Bedraggled. Exhausted.

“If it wouldn’t be too inconvenient, I wonder if we could move to the guest house too.” Gautam now looked as though he’d been punched in the face multiple times by the bad weather demon.

“We just can’t sleep in the tent. We tried,” said Kim, still beautiful and petite on one hour’s sleep in a week.

“Sure, I’ll take you at lunch time. Oh God, I hope the rain backs off for today.” I stared across the garden at the ring of limecrete-filled sacks below. The only good news was, the temperature had dipped significantly.

“There’s no water in the taps.” It was Emma who spoke. She strode over in her Dr Martin boots clutching a cup of herbal tea.

Feryal poked her head out of the door, “Yeah, the water’s been cut off. They’ll turn it on soon.” Then she returned to the kitchen, with her covey of food angels, to rustle up breakfast for 15 people.

I shook my head and laughed, albeit weakly. Because reality was beyond my control, and it had decided to unwind messily. Afternoon came and went in this fractious vein, with Murphy writing all the laws. My shoulders were stiff and aching from carrying the planet around for so long.

By the end of day three, one tent was flooded, one tent had blown away, we had four people now sleeping at the guest house, the water was still off, everyone was beyond exhausted, and we were so far off schedule nothing but divine intervention could save us. I swore I would never EVER do this again.

A house in a week. What had I been thinking? Madness. And now I would pay.

It was on day three we all unraveled. One by one.

I pulled back my tent flap on the morning of the third day to an unpredictable sky. One minute it was a morbid grey shroud, the next a cobalt, sun-emblazoned sheet. The wind whipped the tents. They were canvas contortionists bowing and buckling with each gust. I couldn’t decide if it was a dance or a battle they were engaged in.

The night hadn’t been kind. A brisk deluge at 10 pm had flooded one tent. Its occupant had taken over Kemal’s hammock on the balcony, she was now huddled there hat pulled over her hair, blanket up to her chin. Kemal and Gürkan, the two tent-forgetting late comers from day one, had thankfully possessed the foresight sleep at the guest house.

As I moved toward the house balcony for a coffee, I surveyed the garden. All I could see were skirmishes involving pieces of plastic and earthbaggers who were attempting to keep their tents dry.

Finally, the team assembled in front of the house. Bedraggled. Exhausted.

“If it wouldn’t be too inconvenient, I wonder if we could move to the guest house too.” Gautam now looked as though he’d been punched in the face multiple times by the bad weather demon.

“We just can’t sleep in the tent. We tried,” said Kim, still beautiful and petite on one hour’s sleep in a week.

“Sure, I’ll take you at lunch time. Oh God, I hope the rain backs off for today.” I stared across the garden at the ring of limecrete-filled sacks below. The only good news was, the temperature had dipped significantly.

“There’s no water in the taps.” It was Emma who spoke. She strode over in her Dr Martin boots clutching a cup of herbal tea.

Feryal poked her head out of the door, “Yeah, the water’s been cut off. They’ll turn it on soon.” Then she returned to the kitchen, with her covey of food angels, to rustle up breakfast for 15 people.

I shook my head and laughed, albeit weakly. Because reality was beyond my control, and it had decided to unwind messily. Afternoon came and went in this fractious vein, with Murphy writing all the laws. My shoulders were stiff and aching from carrying the planet around for so long.

By the end of day three, one tent was flooded, one tent had blown away, we had four people now sleeping at the guest house, the water was still off, everyone was beyond exhausted, and we were so far off schedule nothing but divine intervention could save us. I swore I would never EVER do this again.

A house in a week. What had I been thinking? Madness. And now I would pay.

A lesser group would have collapsed on day three. They would have grumbled and whined, and separated into ineffectual back-biting factions, perhaps even run to the beach never to come back. Really.

Respect. It's due.

We arrived at the guest house for dinner. Night was cool. Standoffish. I moved to a table to eat in my own self-persecuting company. The team was a little fragmented as some showered and others ate. I noticed a small ogre of bad feeling making a bid for the group energy. He was a mottled, warted slime of a character loitering just over the brows of conversations, waiting for a chance to sneak in.

But then something happened.

And it wasn’t mud magic.

It was a different kind of spell. The kind we cast the moment we elect to tap into the best in ourselves rather than the worst. The moment we, yes we (not the mud, nor the sky, nor divine intervention) choose our emotional state, and decide to make the optimum happen.

A beer appeared in front of me. Cold, dripping with condensation. I looked up to see Gautam smiling at me. “This one is on me,” he said with such kindness and compassion I nearly cried. The gesture was so poignant. So perfect. Blinking back the tears, I grinned and took a swig.

The team collected in one of the wooden platforms in the garden. The table began to spawn brown bottles. Grabbing my own beer, I kicked off my shoes and climbed the steps to join them.

“Fuck it!” I said collapsing onto the cushions. “I’m drinking tonight!”

My earthbag family cheered. There were pats on the back. The clunking of bottles. Followed by the discussion of the limitations which each of us had had to face; some physical, some emotional, some psychological, some energetic. Because there always is a limit. A point at which we snap. And through those limits we understand ourselves, and our place in the whole.

Taylan roared with laughter. Kim sipped quietly from her glass. Gautam giggled. Emma stretched her back in a yogic half-twist. Canan blew a puff of smoke into the air. Each character was a yarn creating the fabric of our team. And as the beer flowed into the night, the warp and weft of the group tightened. I released the end of each thread and let it find its own way.

Planet Earth slid from my shoulders like a fat, blue football. It rolled into the centre of the platform and out into the garden. It kept on rolling, out of the guest house, through the chasm of the valley until it disappeared from sight.

Now no one was responsible. There was no one to hold it all together. I wondered what would happen.

Respect. It's due.

We arrived at the guest house for dinner. Night was cool. Standoffish. I moved to a table to eat in my own self-persecuting company. The team was a little fragmented as some showered and others ate. I noticed a small ogre of bad feeling making a bid for the group energy. He was a mottled, warted slime of a character loitering just over the brows of conversations, waiting for a chance to sneak in.

But then something happened.

And it wasn’t mud magic.

It was a different kind of spell. The kind we cast the moment we elect to tap into the best in ourselves rather than the worst. The moment we, yes we (not the mud, nor the sky, nor divine intervention) choose our emotional state, and decide to make the optimum happen.

A beer appeared in front of me. Cold, dripping with condensation. I looked up to see Gautam smiling at me. “This one is on me,” he said with such kindness and compassion I nearly cried. The gesture was so poignant. So perfect. Blinking back the tears, I grinned and took a swig.

The team collected in one of the wooden platforms in the garden. The table began to spawn brown bottles. Grabbing my own beer, I kicked off my shoes and climbed the steps to join them.

“Fuck it!” I said collapsing onto the cushions. “I’m drinking tonight!”

My earthbag family cheered. There were pats on the back. The clunking of bottles. Followed by the discussion of the limitations which each of us had had to face; some physical, some emotional, some psychological, some energetic. Because there always is a limit. A point at which we snap. And through those limits we understand ourselves, and our place in the whole.

Taylan roared with laughter. Kim sipped quietly from her glass. Gautam giggled. Emma stretched her back in a yogic half-twist. Canan blew a puff of smoke into the air. Each character was a yarn creating the fabric of our team. And as the beer flowed into the night, the warp and weft of the group tightened. I released the end of each thread and let it find its own way.

Planet Earth slid from my shoulders like a fat, blue football. It rolled into the centre of the platform and out into the garden. It kept on rolling, out of the guest house, through the chasm of the valley until it disappeared from sight.

Now no one was responsible. There was no one to hold it all together. I wondered what would happen.

Bad timing? Canan and Gautam at work...

Part Three - A Team without a Head?

Mustafa the carpenter making some mighty fine door frames.

Mustafa the carpenter making some mighty fine door frames.

By seven thirty in the morning, the earthbag crew had assembled on site. Gone were the grim lines of stratus from the previous two days. The sky was a vault. And it had now opened showering us in gold and lapis lazuli. The land was cupped in the hairy green hands of the forest. All about us large mounds of earth protruded like giant dusty knuckles. That dirt all had to be shoveled into bags and laid on our wall.

“I wonder, do you think there is any chance of us reaching the roof?” It was Gautam who asked. He was standing in the centre of our earthbag ring, head was cocked to one side, jet hair to falling onto his shoulder. It was clear from his intonation, he didn’t have too much faith.

I glanced at the paltry three layers of bags we had laid. We probably had thirty more to go. Not to mention the windows, the shelving, and the dreaded arches. We were almost half way through the course.

Let’s face it. Reaching the roof looked impossible.

Impossible. Such a decisive word. So sure of itself in its despondency. And with so little claim to certainty. For I have witnessed far too many impossibilities become realities.

We all stared mournfully at our measly three layers of wall. The only thing we had going for us was that the door frames had been installed – wonderfully, precisely – by the carpenter. They were invincible frames. Perfectly straight and as thick as girders, with zero propensity for buckling.

I was in one of those moods, though. Conviction was being pumped into me. I pushed out my chin. “Yes there is every chance we can reach the roof. We’re going for six layers today. Anyway, we have back up.” I felt my eyebrows rising as I spoke. Back up. Those famous last words...

“Six layers?” Taylan’s right eyebrow rose a good eight millimetres. He took a large swig of his Nescafe-cola mix, and stared yet again at the metres of thin air above our earthbags.

“Everyone just envisage those six layers finished. It’s going to happen. Come on!”

Emma strode into the circle, cap pulled down, boots kicking the stones. “Six it is,” she said and grinned. Many are those who doubt the physical power of vegans. It was day four and Emma was still striding. Still ready to dig and haul.

Domi, our Hungarian strongman, trotted into the circle with one of our wooden bag holders. He opened the legs and placed it on the dirt ready to begin. I held my hand up, palm facing out.

“There’s one other thing I want to say before we start.”

The group stood around me, a circle of bleary eyes intermittently focusing on the ground, the lack of wall, and me.

“From now on, everyone should just do what they feel like doing. Because if your heart’s in it, it’s the right thing to do. If not, better you don’t do it. If you feel like bagging, do that. If you feel like sitting out and watching, do that. Because on a deeper level we are all plugged in to the same thing, and when we function from there, it works. For everyone.”

It looked like a contradiction. Get to the roof and do what you want? Yet there were murmurs of agreement. Nods and movement. I could sense everyone already had an idea of what they wanted to do. If people are connected to their soul, and they know what they enjoy, what their passion is, it’s easy. Because that passion is derived from their core. And their core is moving in sync with the whole.

The wind jived through the pine trees crowding the steep hill above us. They shimmied and rocked as though following an invisible choreographer. The branches whooshed and rattled in time. As I scanned the forest surrounding the site, it moved as one being. A wave of green needles.

I turned my gaze back to our earthbag circle. A heavy roll of barbed wire, white sacks, shovels, picks, rocks and earth, all began moving. It was coming to life.

“I wonder, do you think there is any chance of us reaching the roof?” It was Gautam who asked. He was standing in the centre of our earthbag ring, head was cocked to one side, jet hair to falling onto his shoulder. It was clear from his intonation, he didn’t have too much faith.

I glanced at the paltry three layers of bags we had laid. We probably had thirty more to go. Not to mention the windows, the shelving, and the dreaded arches. We were almost half way through the course.

Let’s face it. Reaching the roof looked impossible.

Impossible. Such a decisive word. So sure of itself in its despondency. And with so little claim to certainty. For I have witnessed far too many impossibilities become realities.

We all stared mournfully at our measly three layers of wall. The only thing we had going for us was that the door frames had been installed – wonderfully, precisely – by the carpenter. They were invincible frames. Perfectly straight and as thick as girders, with zero propensity for buckling.

I was in one of those moods, though. Conviction was being pumped into me. I pushed out my chin. “Yes there is every chance we can reach the roof. We’re going for six layers today. Anyway, we have back up.” I felt my eyebrows rising as I spoke. Back up. Those famous last words...

“Six layers?” Taylan’s right eyebrow rose a good eight millimetres. He took a large swig of his Nescafe-cola mix, and stared yet again at the metres of thin air above our earthbags.

“Everyone just envisage those six layers finished. It’s going to happen. Come on!”

Emma strode into the circle, cap pulled down, boots kicking the stones. “Six it is,” she said and grinned. Many are those who doubt the physical power of vegans. It was day four and Emma was still striding. Still ready to dig and haul.

Domi, our Hungarian strongman, trotted into the circle with one of our wooden bag holders. He opened the legs and placed it on the dirt ready to begin. I held my hand up, palm facing out.

“There’s one other thing I want to say before we start.”

The group stood around me, a circle of bleary eyes intermittently focusing on the ground, the lack of wall, and me.

“From now on, everyone should just do what they feel like doing. Because if your heart’s in it, it’s the right thing to do. If not, better you don’t do it. If you feel like bagging, do that. If you feel like sitting out and watching, do that. Because on a deeper level we are all plugged in to the same thing, and when we function from there, it works. For everyone.”

It looked like a contradiction. Get to the roof and do what you want? Yet there were murmurs of agreement. Nods and movement. I could sense everyone already had an idea of what they wanted to do. If people are connected to their soul, and they know what they enjoy, what their passion is, it’s easy. Because that passion is derived from their core. And their core is moving in sync with the whole.

The wind jived through the pine trees crowding the steep hill above us. They shimmied and rocked as though following an invisible choreographer. The branches whooshed and rattled in time. As I scanned the forest surrounding the site, it moved as one being. A wave of green needles.

I turned my gaze back to our earthbag circle. A heavy roll of barbed wire, white sacks, shovels, picks, rocks and earth, all began moving. It was coming to life.

***

It was just before lunch when they arrived. And how we grinned when we saw them. With their tight butts and their gleaming six packs, they looked as though they’d hacked their way straight out of Sparta.

This was the Olympos rock climbing squad (a couple of them, at least). Plus a professional female wrestler from Germany. Back up. It was here, and in style.

The sky was yellow and burning now. The sun a fire-lobbing missile. One by one, the back-up biceps stormed down the track to our dirt mountain. And it was here they ran straight into Ayşe.

Ayşe is an old friend of mine, and protagonist of my novel Ayşe’s Trail. She has walked the Lycian Way (all 500 kilometres of it) about eight times now. The first time she did it carrying a twenty kilogram rucksack. All in all, she is fairly unstoppable and something of a maniac.

The moment I had said everyone should do what they wanted, Ayşe had pulled her headscarf over her hair and made for the great hill of dirt. She was standing there now, a five kilogram yogurt pot in one hand, and a polypropylene sack in the other, wiping her brow with the back of her wrist.

“I can’t work in a team! Oof! Look, it’s not right how they’re doing it!” Her sharp blue eyes were gouging holes in the back of one of the mountaineers. He must have felt the burn between his shoulder blades, because he whipped around.

“Hey Ayşe! Why are you using those small buckets? It takes forever! Let’s time it. See which is quicker.” The young man leaned on his spade as he spoke.

“It’s not about timing! You’re doing it wrong. The bottoms of the sacks need to be flattened. You’re just throwing the dirt in.”

Both faces turned in my direction. Both were indignant. “Do the ends need to be flattened?” Asked the mountaineer. He was covered in sweat. His fingers curled around the spade handle, its head buried in a mountain of fresh, brown earth. I shuffled a little, and scratched my chin.

“Well to be honest, we need both square bag ends and speed.” I sighed. “Just do your best.”

Ayşe sniffed and stalked to one end of the dirt pile. The mountaineer shrugged, yanked his spade out and moved to the other. I pulled my phone out of my pocket. The digital clock showed it was lunchtime.

It was just before lunch when they arrived. And how we grinned when we saw them. With their tight butts and their gleaming six packs, they looked as though they’d hacked their way straight out of Sparta.

This was the Olympos rock climbing squad (a couple of them, at least). Plus a professional female wrestler from Germany. Back up. It was here, and in style.

The sky was yellow and burning now. The sun a fire-lobbing missile. One by one, the back-up biceps stormed down the track to our dirt mountain. And it was here they ran straight into Ayşe.

Ayşe is an old friend of mine, and protagonist of my novel Ayşe’s Trail. She has walked the Lycian Way (all 500 kilometres of it) about eight times now. The first time she did it carrying a twenty kilogram rucksack. All in all, she is fairly unstoppable and something of a maniac.

The moment I had said everyone should do what they wanted, Ayşe had pulled her headscarf over her hair and made for the great hill of dirt. She was standing there now, a five kilogram yogurt pot in one hand, and a polypropylene sack in the other, wiping her brow with the back of her wrist.

“I can’t work in a team! Oof! Look, it’s not right how they’re doing it!” Her sharp blue eyes were gouging holes in the back of one of the mountaineers. He must have felt the burn between his shoulder blades, because he whipped around.

“Hey Ayşe! Why are you using those small buckets? It takes forever! Let’s time it. See which is quicker.” The young man leaned on his spade as he spoke.

“It’s not about timing! You’re doing it wrong. The bottoms of the sacks need to be flattened. You’re just throwing the dirt in.”

Both faces turned in my direction. Both were indignant. “Do the ends need to be flattened?” Asked the mountaineer. He was covered in sweat. His fingers curled around the spade handle, its head buried in a mountain of fresh, brown earth. I shuffled a little, and scratched my chin.

“Well to be honest, we need both square bag ends and speed.” I sighed. “Just do your best.”

Ayşe sniffed and stalked to one end of the dirt pile. The mountaineer shrugged, yanked his spade out and moved to the other. I pulled my phone out of my pocket. The digital clock showed it was lunchtime.

Not everyone is about muscle and strength and pushing though. We all come hardwired with different gifts. The question is never what someone can’t do. It’s always what they have to offer.

I’m no longer certain to what extent I believe in the concept of a team ‘leader’. I’m not sure what such a role entails. Because a team functioning from its essence is headless, leaderless. It simply dances all by itself.

To be truly alternative, to genuinely offer another way of existing unlike that which is pushed down our throats by the media, education systems and our cultures, we can’t simply engineer the physical, build new systems, new hierarchies. If we still believe some people, some skills or some attributes are more valuable than others, we are as conformist as the mainstream.

Luckily we had someone to illustrate this point. It was Harika.

“You know, I juss can’t go at zis pace. Iss too much for me,” Harika had said in her light Belgian accent the previous afternoon. She had been lying on her back in the dirt at the time, wheezing unhappily. Harika possessed a graceful character. I would liken it to a cool breeze on a ragingly hot summer day, softly weaving in and out of us as we worked, singing as she went.

Earlier in the day, I had seen Harika moving to the dirt mountain to begin filling bags. Her legs flowed out of a pair of denim shorts. A floppy hat was pulled over her hair. I followed her out of the the earthbag ring. As I approached her, I crossed all eight fingers.

“Harika, I wonder if you can measure the walls.” I knew what we needed more than anything else was a measurer. The walls were flying up now. And when they fly up, they also tend to fly out, or in, or both out and in. The only person measuring was me, and I wasn’t doing it particularly well. In fact I was hopeless. My own mud house is a testament to my failure with regards vertical straightness.

She lifted the brim of her canvas hat. “OK, I can try,” she said. We both turned and stepped back into the centre of the earthbag circle. I walked to the array of pots on the ground, bent and pulled the plumb-line out of a bucket of nails.

Harika took the line in her hand and moved to the inside of the wall. Holding the string up to a tamped bag, she let the weight fall. “Do you have a pen?” She asked. A pen? I wondered what she could want with it.

***

Ten minutes later, Emma and I were dropping a bag onto the barbed wire, when we noticed some red arrows on the polypropylene below.

“Harika, what’s this?” I called out. Our measurer skipped over beaming.

“Iss so you can see if you need to put the bag more in, or more out. And if iss perfect, like this one, then I write it on the bag.”

Genius. The arrows were unambiguous and easy to follow. Harika had even added “1” and “2” to indicate how many centimetres in or out we should lay the next bag. Over the course of the next two days, I tried in vain to find someone else to measure the walls. No one could do it right. Most threw the line down in disgust after five minutes. Unlike my own mud home where the walls had ended up veering out in preposterous amounts, this time we had nothing but minimal bulges.

I’m no longer certain to what extent I believe in the concept of a team ‘leader’. I’m not sure what such a role entails. Because a team functioning from its essence is headless, leaderless. It simply dances all by itself.

To be truly alternative, to genuinely offer another way of existing unlike that which is pushed down our throats by the media, education systems and our cultures, we can’t simply engineer the physical, build new systems, new hierarchies. If we still believe some people, some skills or some attributes are more valuable than others, we are as conformist as the mainstream.

Luckily we had someone to illustrate this point. It was Harika.

“You know, I juss can’t go at zis pace. Iss too much for me,” Harika had said in her light Belgian accent the previous afternoon. She had been lying on her back in the dirt at the time, wheezing unhappily. Harika possessed a graceful character. I would liken it to a cool breeze on a ragingly hot summer day, softly weaving in and out of us as we worked, singing as she went.

Earlier in the day, I had seen Harika moving to the dirt mountain to begin filling bags. Her legs flowed out of a pair of denim shorts. A floppy hat was pulled over her hair. I followed her out of the the earthbag ring. As I approached her, I crossed all eight fingers.

“Harika, I wonder if you can measure the walls.” I knew what we needed more than anything else was a measurer. The walls were flying up now. And when they fly up, they also tend to fly out, or in, or both out and in. The only person measuring was me, and I wasn’t doing it particularly well. In fact I was hopeless. My own mud house is a testament to my failure with regards vertical straightness.

She lifted the brim of her canvas hat. “OK, I can try,” she said. We both turned and stepped back into the centre of the earthbag circle. I walked to the array of pots on the ground, bent and pulled the plumb-line out of a bucket of nails.

Harika took the line in her hand and moved to the inside of the wall. Holding the string up to a tamped bag, she let the weight fall. “Do you have a pen?” She asked. A pen? I wondered what she could want with it.

***

Ten minutes later, Emma and I were dropping a bag onto the barbed wire, when we noticed some red arrows on the polypropylene below.

“Harika, what’s this?” I called out. Our measurer skipped over beaming.

“Iss so you can see if you need to put the bag more in, or more out. And if iss perfect, like this one, then I write it on the bag.”

Genius. The arrows were unambiguous and easy to follow. Harika had even added “1” and “2” to indicate how many centimetres in or out we should lay the next bag. Over the course of the next two days, I tried in vain to find someone else to measure the walls. No one could do it right. Most threw the line down in disgust after five minutes. Unlike my own mud home where the walls had ended up veering out in preposterous amounts, this time we had nothing but minimal bulges.

The shade dripping from the pine trees lengthened. Their boughs turned dark emerald in contrast to the azure above. The definitions between the rocks became more pronounced. They were wrinkled stone hobbits now, their lines giving them both depth and character. It was a striking picture. Perfectly put together.

The land was humming with human activity, and I wandered into the earthbag circle looking for a space to fill. Gautam and Domi were uncoiling the barbed wire in one corner. Canan and Baykal, Emma and Feryal were shoving bags down on the wall in another. Harika was measuring. I moved outside. Taylan was nailing the filled bags closed. Kim was folding sacks. Ayşe and the back up muscle had become a veritable dirt bag factory with tens of ready-filled earthbags lining the perimeter of the wall. Marginally disconcerted, I stood there realising I was utterly redundant.

Having nothing else to do, I squatted next to the wall and began counting the earthbag layers we had laid today. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and a half...

“Six and a half! We’ve done it!” I shouted. Yet I could hardly engender a response. Everyone was too engrossed in their task. Eventually, Taylan wandered in. He had changed into a Batman Tshirt. Standing in the centre of the circle, he stuffed a cigarette in his mouth and lit it. His eyes moved round the earthbag layers. One by one.

“Six and a half rows. And there are on average 42 bags a row. So we’ve filled 252 bags today. Oh maaan! I’ve nailed nearly 252 bags!”

I craned my head back (because Taylan is tall and I’m rather short). Then I stood on tiptoe and patted him on the shoulder. Blowing out a mushroom of smoke, he moved toward the wall. He touched the top layer of earthbags. A frown pushed the fronts of his eyebrows down. Something inside me turned a little cold.

“Uh oh. These are not damp. The earth has gone in dry,” he said sticking a finger into one of the bags.

I closed my eyes. The earth has to go in the sacks damp so that it cures into a clay brick. If it doesn’t, you are simply left with a bag of dry dirt. Ayse had been right. The bag-fillers were going too fast. A prolonged groan moved up from my stomach and out of my mouth. At least half a row was in this dry, loose state. We’d have to take the bags off and start again.

Or would we?

The light turned from gold to silver. The air smelled sweet with evening. And it was then I happened upon an idea. It didn’t crawl into my mind via a dank tunnel from my subconscious, as some ideas do. This one vaulted into my head. If ideas wore clothes, it would have pranced on stage in a sparkling unitard. Quite possibly, grooving to a disco beat.

This idea was pivotal. Little did I realise at the time, it was going to change the entire fundamentals of earthbagging as we knew it.

The land was humming with human activity, and I wandered into the earthbag circle looking for a space to fill. Gautam and Domi were uncoiling the barbed wire in one corner. Canan and Baykal, Emma and Feryal were shoving bags down on the wall in another. Harika was measuring. I moved outside. Taylan was nailing the filled bags closed. Kim was folding sacks. Ayşe and the back up muscle had become a veritable dirt bag factory with tens of ready-filled earthbags lining the perimeter of the wall. Marginally disconcerted, I stood there realising I was utterly redundant.

Having nothing else to do, I squatted next to the wall and began counting the earthbag layers we had laid today. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and a half...

“Six and a half! We’ve done it!” I shouted. Yet I could hardly engender a response. Everyone was too engrossed in their task. Eventually, Taylan wandered in. He had changed into a Batman Tshirt. Standing in the centre of the circle, he stuffed a cigarette in his mouth and lit it. His eyes moved round the earthbag layers. One by one.

“Six and a half rows. And there are on average 42 bags a row. So we’ve filled 252 bags today. Oh maaan! I’ve nailed nearly 252 bags!”

I craned my head back (because Taylan is tall and I’m rather short). Then I stood on tiptoe and patted him on the shoulder. Blowing out a mushroom of smoke, he moved toward the wall. He touched the top layer of earthbags. A frown pushed the fronts of his eyebrows down. Something inside me turned a little cold.

“Uh oh. These are not damp. The earth has gone in dry,” he said sticking a finger into one of the bags.

I closed my eyes. The earth has to go in the sacks damp so that it cures into a clay brick. If it doesn’t, you are simply left with a bag of dry dirt. Ayse had been right. The bag-fillers were going too fast. A prolonged groan moved up from my stomach and out of my mouth. At least half a row was in this dry, loose state. We’d have to take the bags off and start again.

Or would we?

The light turned from gold to silver. The air smelled sweet with evening. And it was then I happened upon an idea. It didn’t crawl into my mind via a dank tunnel from my subconscious, as some ideas do. This one vaulted into my head. If ideas wore clothes, it would have pranced on stage in a sparkling unitard. Quite possibly, grooving to a disco beat.

This idea was pivotal. Little did I realise at the time, it was going to change the entire fundamentals of earthbagging as we knew it.

See Ayşe, Gürkan, and Taylan in this short how to video on Youtube. (Shot by Emma)

Stars of Part Three:

Part Four - The Arch

Gürkan and Taylan getting on with it.

Gürkan and Taylan getting on with it.

“I need some water. Someone bring the hose.” Evening was upon us. The shadows were dying now, their thin outlines dissolving into the dusk. The buzz of the crickets ebbed, and the forest twittered with feathery life hunting for a roost. I turned to see Gürkan dragging the green snake of a hosepipe over the dirt towards me.

Gürkan was the other tent-forgetter who had arrived late the first night with his friend Kemal. The two of them were as physically disparate as you could imagine. Kemal was an ebony Titan, while Gürkan was a bantam weight action man. They were like Batman and Robin without the tights.

“Look, the earth inside the bags is dry. See?” I said digging my index finger into the mesh again. The wall came up to my shoulders. Gazing over it I saw Gürkan peering across at me, eyebrows rising quizzically. Behind him ramparts of ochre earth climbed up to the trunks of the forest. He said nothing. Which was typical. He was a doer not a talker.

“Soo, the plan is to wet the bags on the wall. The bags are permeable so they should absorb the water. The only question is will the earth get damp all the way through?”

“Hmm.” Gürkan’s hand reached for his goatie. His other hand passed me the hose.

In another life in Istanbul, Gürkan had been a very successful techie at Turkey’s largest telecommunications group. Here and now in the earthbag workshop, he was everyone’s right hand man. You will notice him on nearly every video, a silver-haired fellow with a tattoo quietly getting on with things. Because he was always there.

Stretching my arm over the wall, I turned the tap. Water gushed onto the bags. It bubbled on the top of the white polypropylene skin before seeping inside. I let the tap spurt for a while, allowing the bags a good drenching. Then I turned off the spigot and threw the plastic cable to the ground.

“If the bags aren’t wet enough, we’ll have to pull all these off and rebuild.” I said feeling the freshly hosed bags. Then I stood back a little and exhaled. “I think we’ll only know the truth after we’ve tamped.

My silver assistant disappeared from view. All I could see was a grey scalp moving behind our sack wall as he searched for the tamper.

***

Five minutes later, Gurkan was standing at the far end of a freshly tamped wall, pointy beard split by a smile. He squatted and ran his hand along the top of the bags. “Seems hard,” he said.

I moved forwards and tried to dig my fingers in the earthbags. But I couldn’t. The sacks had been transformed into solid bricks of mud. Elation flapped its wings and became airborne within me. I cheered and whooped.

“It worked! Oh my God it worked! Do you know what this means?”

Gürkan stood up and remained stock-still on the wall, waiting.

“It means we don’t have to wet the dirt before it goes in the bags anymore! Think how much easier it’s going to be to lift dry bags!” And with that I scrambled up the wall to call a meeting. This was the best news I’d seen since the mountaineering team’s biceps. And to think, if that ‘mistake’ of not dampening the earth enough hadn’t been made the previous day, we’d never have known there was another way.

Dusk was now so deep, it was brushing the edge of night. Yet within that dimness, the rocks in the dirt came to life. The facets of their knurled bodies glowed in the twilight, until they were no longer obstructive hunks of matter, but shimmering moonstones.

But of course, tomorrow was another day. And with each fresh orbit of the planet, there are new adventures, new earthbag hillocks to climb, and invariably new things to go wrong.

Gürkan was the other tent-forgetter who had arrived late the first night with his friend Kemal. The two of them were as physically disparate as you could imagine. Kemal was an ebony Titan, while Gürkan was a bantam weight action man. They were like Batman and Robin without the tights.

“Look, the earth inside the bags is dry. See?” I said digging my index finger into the mesh again. The wall came up to my shoulders. Gazing over it I saw Gürkan peering across at me, eyebrows rising quizzically. Behind him ramparts of ochre earth climbed up to the trunks of the forest. He said nothing. Which was typical. He was a doer not a talker.

“Soo, the plan is to wet the bags on the wall. The bags are permeable so they should absorb the water. The only question is will the earth get damp all the way through?”

“Hmm.” Gürkan’s hand reached for his goatie. His other hand passed me the hose.

In another life in Istanbul, Gürkan had been a very successful techie at Turkey’s largest telecommunications group. Here and now in the earthbag workshop, he was everyone’s right hand man. You will notice him on nearly every video, a silver-haired fellow with a tattoo quietly getting on with things. Because he was always there.

Stretching my arm over the wall, I turned the tap. Water gushed onto the bags. It bubbled on the top of the white polypropylene skin before seeping inside. I let the tap spurt for a while, allowing the bags a good drenching. Then I turned off the spigot and threw the plastic cable to the ground.

“If the bags aren’t wet enough, we’ll have to pull all these off and rebuild.” I said feeling the freshly hosed bags. Then I stood back a little and exhaled. “I think we’ll only know the truth after we’ve tamped.

My silver assistant disappeared from view. All I could see was a grey scalp moving behind our sack wall as he searched for the tamper.

***

Five minutes later, Gurkan was standing at the far end of a freshly tamped wall, pointy beard split by a smile. He squatted and ran his hand along the top of the bags. “Seems hard,” he said.

I moved forwards and tried to dig my fingers in the earthbags. But I couldn’t. The sacks had been transformed into solid bricks of mud. Elation flapped its wings and became airborne within me. I cheered and whooped.

“It worked! Oh my God it worked! Do you know what this means?”

Gürkan stood up and remained stock-still on the wall, waiting.

“It means we don’t have to wet the dirt before it goes in the bags anymore! Think how much easier it’s going to be to lift dry bags!” And with that I scrambled up the wall to call a meeting. This was the best news I’d seen since the mountaineering team’s biceps. And to think, if that ‘mistake’ of not dampening the earth enough hadn’t been made the previous day, we’d never have known there was another way.

Dusk was now so deep, it was brushing the edge of night. Yet within that dimness, the rocks in the dirt came to life. The facets of their knurled bodies glowed in the twilight, until they were no longer obstructive hunks of matter, but shimmering moonstones.

But of course, tomorrow was another day. And with each fresh orbit of the planet, there are new adventures, new earthbag hillocks to climb, and invariably new things to go wrong.

The sun was a golden umbrella over the site, the pine-covered walls of the valley reaching up towards it. And within this cocoon of earth, trees and sky a house was being born.

It was mid-afternoon, and we were racing up the wall at an unbelievable pace. I have, quite honestly, never seen anything like it. More mountaineers had arrived now, drawn by tales from their peers. And the dirt mountain, under the tutelage of mountaineer Güneş and hiker Ayşe, was churning out filled earthbags like an open air sausage factory.

There was another development, too. Ayşe had now acquired an accomplice, Derya.

“I hope you’re filling the bags properly.” Ayşe’s eyes bored like a couple of steel drill bits.

“I’m doing it very properly!” Derya knelt in the dirt, hands on hips, thick fleece of brown hair harnessed by a hair band.

“The ends aren’t square enough!”

“Yes they are. Very square. That’s as square as they need to be.”

“Well I don’t think they’re square enough.”

“Well I do.”

At almost 50, Derya was our most ‘senior’ participant. Normally, she was a park developer for Ankara city council, and rather excitingly planned to incorporate earthbag buildings into her next urban project. I had to hand it to Derya, she was a tough cookie. Back on the second day, her tent had suffered a wash out. She’d spent the past two nights sleeping in the hammock, woolly hat pulled over her thick mane. But it hadn’t killed her off. No doubt, years of duelling against the dark forces in municipal politics had made her impervious to pain.

Now diehard Derya, out of good will or sheer obstinacy or both, had taken up residence next to Ayşe. I could see them both from my perch on the earthbag wall, butts in the dirt, surrounded by yoghurt pots, scrabbling in the soil like a pair of sharp-tongued moles.

As afternoon progressed, the sun skidded toward the peaks. The forests had been carved into sculptures by its golden blades. Our site was now bathed in a renaissance light, turning the earthbag workshop into a chiaroscuro masterpiece. Everywhere I looked, people were either throwing earthbags on the wall, tamping or engaged in a seemingly never-ending paso doble with barbed wire. It was quite something to watch.

And then we reached the arched windows.

“Erm, everyone gather round.” I stood just outside the door frame, the earthbag wall behind me now reaching my head. Sitting atop the wall were two beautiful organic semi-circular frames. They had been created by our carpenter Mustafa who had hollowed out the inside of a tree, cut it in half and mounted the two halves on lintels.

Slowly, reluctantly, the team left their work stations. The sun dipped below the tip of a pine tree, and the light was instantly altered. Suddenly, the earthbag wall was transformed into an insipid backdrop of polypropylene.

As the group congregated around me, I cleared my throat. “We are going to make an arch. Well two arches in fact, to go around these frames. Now, I fully admit I’ve never done this before.” As I spoke, I noticed one or two raised eyebrows in the crowd. I shuffled in the dirt.

“Why do we need an arch? Can’t we just earthbag straight over those wooden semi-circles?” Derya asked. She was still holding an empty earthbag. It rustled slightly when she moved.

“Because when we tamp the bags, the wooden frame will crack. It’s too thin.” I knew this from much cracked lintel experience gleaned from my own mud home. Earthbags are very heavy. Tamping them exerts an enormous pressure on whatever is below. 'The arch is architecture’s strongest structure,” I added, which was probably the most I knew about it.

“So how do we make an arch?” It was Kemal who asked. He towered over the rest of the group in a white T shirt.

“What we need is to make earthbags that are wedge-shaped, and then build them around our wooden frame.”

“And how are we gonna do that?” Asked Taylan, hands on hips at the back of the crowd, before reaching into his pocket and lighting another cigarette.

I sucked in my breath. “I don’t know. As far as I can tell from the earthbag bible, we have to mold them somehow. Let’s go to the dirt mountain and give it a go.”

There were a few murmurs of dissent, and a lot of rumpled foreheads. Everyone was thinking. Which was fortunate, because by the end of the day we’d need every single brain cell we could lay our grime-streaked hands on.

When I reached our hill of ploughed soil, I knelt in it. The earthbag team formed a wonky circle around me. All I could see was an array of battered footwear and dusty toenails. I opened an earthbag. Ayşe stepped forward to pour a pot of damp soil in. Squashing it down with my fist, I tried to create a wedge shape from it. But the earth kept breaking up. It refused to hold its form. I could hear a little naysaying starting to rumble through the team. “Snot gonna work, snot gonna work.”

Suddenly Emma-the-vegan-yogi moved alongside me holding a couple of wooden slats she’d found on site. “Look!” she said, angling the slats between her Doc Martins to create a wedge form. “Let’s try filling the bag in here.”

It was a great idea. I shuffled over with my earthbag and slotted it into the makeshift wooden mold. Thrusting my fists into the bag, I pummelled the earth into the corners. Finally, I lifted the sack from the ‘mold’. It was a definite improvement on the first effort, firmish, but still not firm enough.

It was mid-afternoon, and we were racing up the wall at an unbelievable pace. I have, quite honestly, never seen anything like it. More mountaineers had arrived now, drawn by tales from their peers. And the dirt mountain, under the tutelage of mountaineer Güneş and hiker Ayşe, was churning out filled earthbags like an open air sausage factory.

There was another development, too. Ayşe had now acquired an accomplice, Derya.

“I hope you’re filling the bags properly.” Ayşe’s eyes bored like a couple of steel drill bits.

“I’m doing it very properly!” Derya knelt in the dirt, hands on hips, thick fleece of brown hair harnessed by a hair band.

“The ends aren’t square enough!”

“Yes they are. Very square. That’s as square as they need to be.”

“Well I don’t think they’re square enough.”

“Well I do.”

At almost 50, Derya was our most ‘senior’ participant. Normally, she was a park developer for Ankara city council, and rather excitingly planned to incorporate earthbag buildings into her next urban project. I had to hand it to Derya, she was a tough cookie. Back on the second day, her tent had suffered a wash out. She’d spent the past two nights sleeping in the hammock, woolly hat pulled over her thick mane. But it hadn’t killed her off. No doubt, years of duelling against the dark forces in municipal politics had made her impervious to pain.

Now diehard Derya, out of good will or sheer obstinacy or both, had taken up residence next to Ayşe. I could see them both from my perch on the earthbag wall, butts in the dirt, surrounded by yoghurt pots, scrabbling in the soil like a pair of sharp-tongued moles.