|

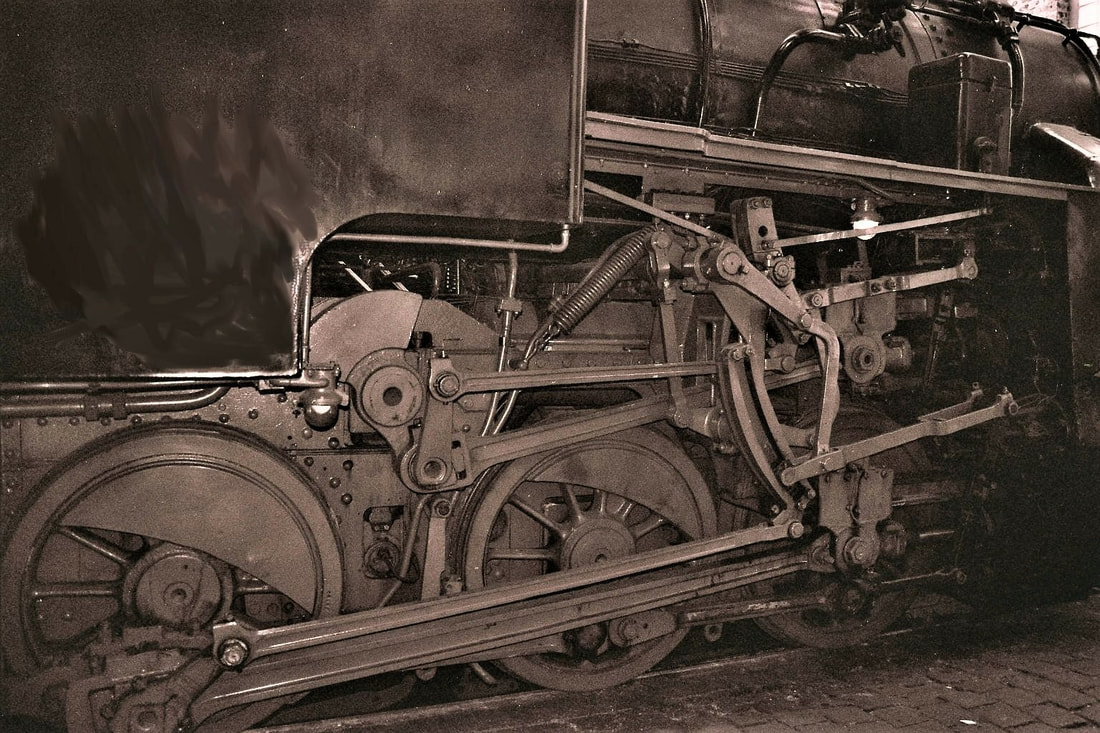

I was awoken by an ethereal chime. Blinking, I rolled over in the warm nest of my duvet. It was my phone. A few muscles in my torso lurched and yanked themselves to attention, because I knew who it was. The foreign police office. Hesitating a moment, I let the phone ring one more time while I gathered my wits and my words. It’s bad enough dealing with a bureaucrat when you’re fully conscious, but duelling with administration in a language you’re still rather inept at, when you’ve just woken up? I didn’t rate my chances too highly. “Hola!” I tried to sound chirpy. “Esta la señora Bingham?” “Si si!” And thus el señor Foreign Police Officer began to put me through my paces. “I’m sorry, we can’t accept this insurance policy,” he said. I repeated back to him to make sure I’d understood correctly. “No acceptan?” “No.” “Por qué?” “Because there is a limit in this policy for the days in the ‘ospital. And no enough coverage for expenses.” I was caught between teeth gnashing despair at the fact that I still – after three weeks of slog – hadn’t cleared the insurance hurdle in my residency gauntlet, and glee at the realisation that I had understood everything he’d said. At the very least, these dealings were good Spanish practice. “So what is an acceptable limit for expenses?” I pushed on, determined to eke some irrefragable information out of the call. “Hmm, no es concreto.” “No es concreto? So how did you decide this policy wasn’t okay if there’s no concrete rule?” I sat up in bed and fought the urge to lob my phone at the door. “Well, it’s a bit low.” I breathed slowly and deeply, and tried to circle my opponent. “Right, so just for the sake of argument, roughly what figure would you count as not low?” El señor of the pencil-pushers wasn’t so easily cornered. Politely and carefully, he voiced his conclusive response. “I don’t know.” Aghhh! I could feel something hot and bitter rising in my guts, so I dug my heels in a little deeper. Hell! At the very least I had to make a dent in the bureaucratic machine, wedge a small spanner in between its mindless whirring cogs, a toothpick even. “Right. But you must have seen insurances before and passed them. So can you tell me a company which offers health insurance that you like?” There was a pause. El señor seemed to be scratching his head. “To be honest, I haven’t seen this before. Most of the people ‘ave official jobs or are students, so it’s different.” I crashed back on my pillow and pulled my duvet up to my chin, before admitting defeat. I’d not even achieved the tiniest of chinks in the armour. Not so much as a scratch. When you’re an independent attempting to slip between the soul-shredding wheels of The System, you have to be nothing short of a ninja to find a gap. I hadn’t found it yet. Groaning to the very depths of my being, I hung up. I’m no greenhorn when it comes to residency applications. This is the fourth I’m obtaining in my life, and it’s always a protracted kind of torture for an immigrant, because desk jockeys the world over live in an alternate universe in which neither reality nor humans matter. It’s a blip in the space-time continuum where the only truth is boxes on forms, ticks, stamps, and signatures. As I flung the duvet back and huffed my way into the bathroom, I uttered a few expletives. Though I did still have my favourite weapon lurking up my dirt-filled sleeve. Stubbornness. If you can just hang on and keep pushing long enough, sometimes, just sometimes, even The System’s pistons break under the strain. The following week I trawled every insurance broker in the vicinity, collecting policies. The company whose policy I’d already signed up for agreed to change theirs to limitless days of hospitalisation too, all while shaking their heads and muttering that they’d issued at least three hundred of these to residency seekers and never seen a demand like this before. Soon I was ready. I flexed my fingers, limbered up, and prepared myself for my fourth trip to the big city in two weeks. Now, government offices in Spain run on interesting timetables. In fact, everything in Spain does. Opening and closing times are arbitrary and idiosyncratic, the windows for action incredibly narrow. I’m surprised they haven’t made an app for it. “Esta ‘app’ierto?” is an opportunity just waiting for a Spanish techie. For building permits, for example, the office in my locality is open between exactly 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. on a Tuesday or Thursday. That’s it. Turn up on Friday, and you’re stuffed until Tuesday. The Foreign Police (an hour’s drive away) grace us with their mostly grumpy presence between 9 a.m. and 12 noon. I’m telling you, hitting these official slots requires dedication of focus. Twas just over a week ago, and after a sleep-deprived drive through the rush hour traffic of Gijon, I parked up and began the now-familiar hike to the Foreign Police Department. It was freezing, the air caking onto my cheeks in icy wads. Soon enough, I was sitting on the half-broken chairs, clutching my number, along with a cohort of other disenchanted residency seekers: The Syrian sisters who cackled loudly behind me, the pretty Chinese student who glared in silent fury at the inefficiency, the young Nigerian chap who was so agitated he kept walking up to the desk, and then would be ordered to sit and wait a bit more. I’m an old hand at this game, but even so. All the Zen in the world doesn’t detract from the psyche-mauling truth that despite not being a criminal you’re wasting days of your life being treated like one. Days. Weeks. I tried not to think about it as I waited and waited and waited for my number to be called (because the electronic number system was broken and no one knew who was supposed to go when). Finally my moment arrived. The weary young woman who inevitably supervises the extranjero desk sighed when she saw me, and I took some pleasure in that. Was I wearing her down? I thrust the five policies under her nose, and asked her which would be acceptable. She gathered the papers and disappeared behind a door, presumably to ask el señor of the early morning wake-up call. Minutes passed. More minutes passed. I closed my eyes and meditated. Finally she returned. “No. No. No. No.” The policies struck the desk one by one in disappointing thuds. She shook her head gravely, and then raised a couple of hairs in her right eyebrow. “But we could accept the old policy if they add ‘no limit of ‘ospitalization’ on it.” “What about the expenses being too low though?” I asked. She shrugged and cocked her head in the direction of the secret inner office. “He said it’s okay, but you must come back with this new policy, and a receipt from your bank to show you’ve paid it.” I nodded. And oh how happy I was, as I danced out of the Police Department for a coffee and a tortilla. Alas! My jubilation didn’t last long. The next day I drove to my insurance broker (in another town in the wrong direction) to collect my documents. Now, I always try to be generous about people in my writing, but I’m afraid in this case exasperation wins. Hasan the insurance broker was one of the most incompetent lumps I’ve ever had the misfortune to deal with. Truly, I exaggerate not. It would take a good five WhatsApp messages to clarify exactly when he’d would be in his office, and even then I’d turn up and two out of three times he wouldn’t be there. This time, after climbing the office stairs and pushing the 1980s shiny wooden door open, I was amazed to find the man actually in the office. He briefly flicked his head at me, and began distractedly printing off the new policy details while blabbing on the phone to his friend. “I need a receipt,” I said, when eventually he hung up. “You get it from the bank.” “Yes but it was a week ago and the payment still hasn’t gone through! Can you call the company and find out why?” “Oh it will happen, don’t worry.” Hasan waved me away. So I waited another week. As you do. Nada. Not so much as a cent moving from my account. So I inhaled deeply, and made the journey yet again to Hasan’s office (the 7th so far), because if you don’t see people face to face, nothing happens. The rain was driving hard, and by the time I’d walked through the town, my jeans were wet through and my boots were squelching. I entered the wood clad room bedraggled and dripping. Naturally, Hasan wasn’t there. So I took a seat and explained my predicament to his colleague. “How strange. The payment should have gone through. I wonder if there is a mistake,” the young woman said. “I’m sure there is a mistake,” I replied, pulling off my coat and wondering if the steam billowing out of my ears was visible yet. Hasan’s colleague scanned through the policy, soon pulling out the IBAN number of the account that had been charged. The problem was obvious even from my side of the desk. “I don’t know where he got that number from, but it isn’t mine.” “Not your IBAN?” “No.” At that moment, useless Hasan entered the office. His colleague waved the paperwork at him and expounded the details of his cock-up. Meanwhile a terrible feeling stole through me, because I thought I knew where Hasan had found that mistaken IBAN number. Flicking hastily through my bank transfer receipts which he was supposed to copy my account details from, I soon found the one I was looking for. I’m afraid, this is the moment I lost it. There is only so much patience a human possesses. Only so much. Standing up, I pulled my index finger out, feeling six weeks of frustration rising up and pouring out through my eyeballs. “Look Hasan, you’ve copied my landlady’s IBAN number onto that policy instead of mine!” I so wanted to add, “you lazy, deficient half-wit!”, although I think that point was probably conveyed telepathically. Hasan mumbled and blathered a bit, gaped at the numbers as though they were figures in some arcane sudoku puzzle, and finally said, “yes I see. You’ll have to call her and tell her to return the payment.” “No Hasan.” I said, still standing. “You have to call her. Right now.” He shifted and squirmed, before pulling out his phone. I could see the sweat forming around his hairline. His colleague lowered her head, and the room turned rather quiet. That night I drove back to the coastal town I’m holed up in for winter, still fuming. The moon was full and eclipsed, or so I heard, because the Asturian sky was thickset with clouds rendering the more distant movements in the solar system invisible. As I walked to my door, I huddled to fend off the rain, which was driving even harder than before. It was just before midnight when I peered out of my window and saw something odd sticking out of the river. It looked like a massive metallic elbow. Opening the latch for a better look, I realised the water level had risen preposterously high, and that the river was roaring. A crowd of people had gathered at the bank too. Something was afoot. The rain continued to hammer down throughout the night. It was a gnashing snarl of a downpour, the likes of which I’d never witnessed here before. I awoke the next morning to see that the river had burst its banks and flooded the road. In fact, every major river in Asturias overflowed that day. Towns were evacuated. Roads closed. I saw the wayward metallic elbow was in fact the canoe jetty and gang plank which had been completely ripped out, and were swaying upended in the river. As I gazed at the sheer power present in the cascade of the river, suddenly I felt grounded in a way I hadn’t for weeks. Because there is a higher authority than The System and its desk-bound army. There is a higher authority than the ruling elite, too. As I listened to the drum of the rain, I mulled it all over. I’ve spent six weeks (about three or four days a week), have driven over 1000 kilometres, and spent about 800 euros, trying to legalise my status. And I still don’t possess the idiotic photocard that The System erroneously thinks proves my existence. Am I coming full circle? Because I’m remembering Mud Mountain, and why I shifted off-grid in the first place. There comes a point when the risk of being non-legal becomes far easier to survive than the pain of the bureaucratic process itself, you see. Once freedom has been tasted, you don’t opt for the chicken coop again, Europe, UK, or otherwise. *** The tide has pulled back now. The water level has receded. But as I watch the resident flocks of white egrets happily taking advantage of the freshly wetted meadows, and the migrant storm petrels fishing (without papers) out at sea, I wonder how we humans got ourselves into this enslaved mess. My land is waiting just up the road with her three water sources, her bounteous earth, her wood to burn, her rocks to build with. She cares not a hoot about jurisdiction and cards and obedience. Her only demand is relationship. Ah poor, old, decrepit System. Don’t cry if we leave you behind. You are unable to evolve, unable to adapt. Your steel claws are becoming blunter, your promises of security lamer by the day. How long before you lose us completely? How long? If you find inspiration in this blog and The Mud Home site, and would like to express that you want it to continue, please consider making a pledge on Patreon to support it. For just $2 a month you join my private news feed, where I post photos and musings I don't wish to share with the world at large, plus a monthly patron-only video from my land.

Many thanks to the dear Mud Sustainers, and all those already contributing on Patreon. You keep this blog alive.

17 Comments

|

Atulya K Bingham

Author, Lone Off-Gridder, and Natural Builder. Dirt Witch

"Reality meets fantasy, myth, dirt and poetry. I'm hooked!" Jodie Harburt, Multitude of Ones.

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed